1944-08-29

Avro Lancaster B.I - Serial # LL947

300 Squadron, Faldingworth

Colorprofile by Ingemar Melin

- F/O David Jones, Pilot

- Sgt Georg Bayless, Flight Engineer

- Sgt Andrew Hendry, Navigator

- Sgt Vernon Condon, Wireless Operator

- F/S John Tovey, Bomb Aimer

- Sgt Stephen McFarlane, Mid-Upper Gunner

- Sgt John Witworth, Rear Gunner

The hatch, the history of Lancaster LL947

- Written by Rolf Arvidsson -

Since my early childhood aviation has been a great personal interest of mine. My parents had a farm in the village Ålstorp in southern Halland, about 10 km east of Laholm. I was born in 1942. In the late 40´s and 50´s this place was a fantastic viewing point if you wanted to see aircraft. The Air Force squadrons, F10 and F14, in Ängelholm and Halmstad flew with their planes several times daily. And other aircraft passed as well. It was the J22, J21, B18, B3 and even "blow torches" such as J21R and J28, and then the "monster" - the J29 Tunnan (flying barrel). Even "those yellow ones", from F5 Ljungbyhed, passed from time to time during training flights over southern Halland. The most dramatic incident was when a group of B18 came flying at extremely low altitude. The pilots waved at us and we even felt the wind as they passed by.

A three year older friend of mine was a big fan of aviation and he tought me many things. He in turn had a friend who sometimes came to visit. His name was Jan-Olof Molin (1935-2005). He lived in Bjärnum and is well known among aviation historians. His models was fantastically well made.

In the village we formed a model flying club in a former servants´ chamber which was heated with a iron stove. The smell from the stove blended with the scents of hobby glue, paint and Semo dope. Catalogues from Wentzels and Sven E. Truedsson were our Bibles.Sigurd Isacson was a prophet and Biggles was God. The floor was at times full of balsaspill and clips from Japanese paper. Most of what we built was not good, but it burned very well. We fixed a crash in a field with fire and everything, and documented the drama with a box camera that gave black and white images. I did not like it when my old friends Spitfire met this cruel fate. The coolest thing was when mentioned friend got a line controlled model aircraft with a 1.5 cc Frog diesel engine. The engine ran on a mixture of ether, castor oil and kerosene. ’That was the right stuff’ we thought!

THE HATCH - the story from the beginning

, , , , , , , . the Home Guard,During my childhood a mysterious HATCH with the text Emergency Exit hanged in one of the farm´s outhouses. It had been put there by my father in the autumn of 1944. Since I was only two years old at the time I knew nothing about it. But later on, when I was a bit older, THE HATCH got my curiosity. I had heard fragments of dramatic stories when THE HATCH was mentioned. There was talk of Night, Darkness, Fire, Bombers, Explosions, Aviators, Parachutes, Machine Guns and other things, words that sent shivers down the spine on a kid like me. Some times also mentioned was The Swedish Home Guard, Four-engines and Flying Fortress.

|

|

|

|

| |

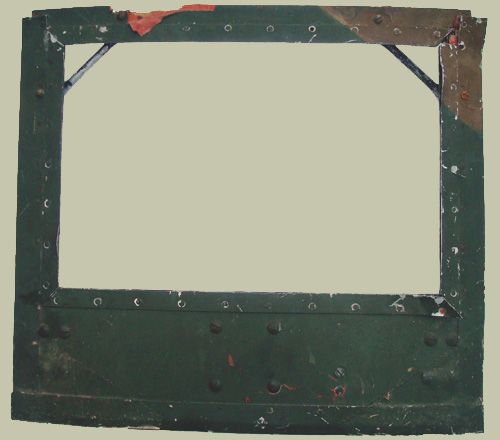

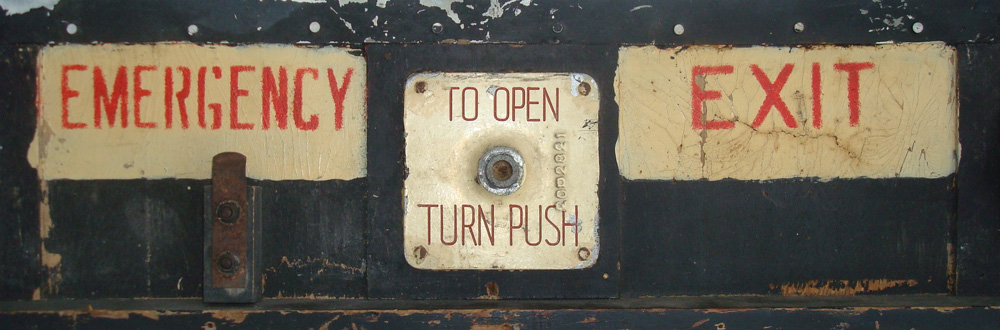

The hatch (54 x 48 cm), inside and outside. The hatch is now a part of the FLC:s collection. Photo © Nicklas Östergren.

The research begins

THE HATCH hanged on the same place in my parents home for a few decades and we basically forgot about it. It wasn´t really until 1980 before I decided to find out all the facts about the crash in 1944. First I contacted the local newspaper - Laholms Tidning. They in turn contacted the local aviation historian Torkel Fagerström who in his turn contacted Bo Widfeldt. The latter had already then, thirty years ago, put together an impressive body of facts about forced landings during the war. The articles that the newspaper published in November 1980 had the result that quite a few people with personal recollections of the crash 36 years earlier got in touch with me. The picture of what had happened in 1944 became clearer. However, to sift the stock, myths and tall stories are always trying to creep in among the facts in such dramatic stories.

But now at last I had some good information to continue my search with. It was not a Flying Fortress that had crashed, but a British Avro Lancaster. The accident had occurred on the night of August 29/30, 1944, in the forest about 6 km northeast of my home. I got in touch with the Royal Air Force and its Air Historical Branch via mail. The RAF was very helpful and sent a lot of information, and also gave me reference to relevant litterature.

Avro Lancaster Mk. X, FM213. Today, there are only two airworthy Lancasters in the world. FM213 is based in Canada.

In June 1984 I wrote a summary of what had happened. Between 1980 and 1984 I tried in a number of ways to get in touch with the seven airmen, but failed. It was a big disappointment for me. All had survived the crash by parachute jumps. One of the crew had also returned to the crash site in 1959, but I did not know about it untill much later.

Facts

The bomber belonged to the Royal Air Force Bomber Command and was an Avro Lancaster Mk.1. Its serial number was LL947. It was labeled BH-W, where "BH" was the code for the 300th Squadron and "W" (William) was the identity for this particular aircraft.

The crew of LL947:

-

The pilot and ’Skipper’: Flying Officer David Jones

-

Flight Mechanic: Sergeant George Bayless

-

Navigator: Sergeant Andrew Hendry

-

Radio Operator: Sergeant Vernon Condon

-

Bombardier and nose turret gunner: Flight Sergeant John Tovey

-

Top turret gunner: Sergeant Stephen McFarlane

-

Tail turret gunner (’Tail-end Charlie’): Sergeant John Whitworth

The age of the crewmen were about twenty years, except for the radio operator, Sergeant Vernon Condon, who was still in his teens.

The flight mechanic´s duties was to assist the pilot with the throttles during takeoff and landing. During the flight he would keep an eye on the gauges, for example oil pressure and oil temperature and coolant. Furthermore, he would check the fuel consumption and manage the controls for the fuel pumps and selectors for the different gas tanks. In the event of an emergency, he could also take over as pilot.

The navigator had maps and several instruments to help him keep the bomber on course. Adjustments must be made with consideration to the prevailing wind direction and strength.

>The radio operator sent and received messages. He would also monitor the bombers intercom and electrical systems. The microphone to the intercom was located in the oxygen mask.

The bombardier directed the pilot during the last stretch towards the target and then dropped the bombs. He lay on the floor at the front of the bomber where the bomb sight was placed. During this phase of the mission it was important for the pilot to fly in an straight line without any evasive maneuvers. This was one of the most vulnerable moments throughout the entire raid. The bombardier also acted as gunner in the nose turret.

Among the gunners the tail turret gunner was the most isolated crewman. His place was extremly cold and draughty. His only contact with the rest of the crew during missions was via the intercom.

Pilot's seat in a Lancaster

A crew in front of their Lancaster. However not the crew of LL947.

The mission

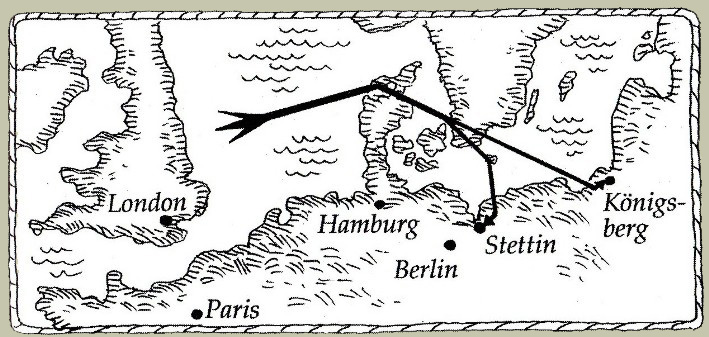

On the evening of Tuesday August 29, 1944, the Royal Air Force Bomber Command ordered nearly 600 Lancasters to take off from various bases in the United Kingdom. The bombers would participate in two major raids. The first group, with about 200 bombers, had the port and city of Königsberg in East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia) as its target.

The second one took off a little later and was much bigger. It included more than 400 Lancasters. The target was another port city by the Baltic Sea - Stettin by the River Oder (now Szczecin, Poland). This was the target for Lancaster LL947 and its crew.

The war situation now at the end of August 1944 was that the Western Allies finally managed to boost its ground offensive after the slow start in Normandy. Paris was liberated and in the southwest the allies had almost reached the river Loire. A quick thrust to the northwest liberated Brussels and Antwerp in early September.

To the east the Soviet Red Army had pushed its way into the Baltic states and threatened East Prussia. And was now standing just east of Warsaw. The two air strikes against the port cities of Königsberg and Stettin were meant to target the ports and disrupt shipping so that among other things Sweden recognized the great risks involved in trading with the Germans over the Baltic Sea.

During the evening, 21:15 local time, Lancaster LL947 with its crew took off from Faldingworth in central England (which was the home for 300th squadron.) During the war the brittish used double summer time. Meaning that the time in Sweden was 20:15 at the time. The bomb load consisted of one 4000 lb (1816 kg) bomb. This bomb was called "cookie" or "Blockbuster". The rest of the bomb load consisted of incendiary bombs, namely 1050 x 4 lb (1.8 kg) and 84 st 30 lb (13.6 kg). Total bomb weight was approximately 4870 kg.

The flight route that night was the same for all the hundreds of bombers on their way to the two Baltic cities. They crossed the North Sea, Jutland, Kattegat, south-western Sweden, and finally over the southern Baltic towards the two targets. The German air defenses in Jutland were used to enemy bomber streams and was quickly alerted when the bombers against Königsberg arrived. To their help the germans had ground-based radar and the night fighters were equiped with airborne radar. With the support of these systems the germans located individual victims of the bomber armada. Soon came the first losses on both sides. Planes were shot down and crews lost their lives in this cruel struggle.

Over southwestern Sweden peoples sleep were disturbed by the mighty roar from hundreds of heavily loaded four-engine bombers that poured in from the west. This was in itself nothing new, but many who experinced it felt that this night between 29 and 30 August 1944 was perhaps the most dramatic of the entire war.

Already when passing over Jutland Lancaster LL947 recieved such serious damage that a fire broke out in one of the outer engines. After another attack from a night fighter the other outer engine bursted out in flames. Over the Kattegat, towards the Swedish west coast, the skipper David Jones realized that their mission must be aborted. Return to base was not a realistic option. Thus remained to make an emergency landing or bail out over Sweden. Since LL947 with its heavy and dangerous cargo lost altitude the bombs were jettisoned in the Kattegat before they flew in over southern Halland - just south of Halmstad. It was impossible in the dark to find a place to land, therefore Jones ordered the crew to bail out. Eyewitnesses on the ground have described how the burning aircraft made several dramatic course changes. During this rickety ride over wooded areas the crew left the doomed Lancaster and bailed out into the darkness. Shortly after the last crewman had left the bomber it crashed into a beech wooded hillside near the Hultabygget, about 6 km southwest of Knäred. The large aircraft skidded on the tops of the trees and plowed a 100 m long furrow in the beech forest. The rear of the fuselage was ripped off during the crash and was left hanging on some broken tree trunks. The nose and the four engines made deep craters on the hillside and in the following fire the explosions from ammunition could be heard far and wide in the night. Lancaster LL947's last mission was over, although not by bombing Stettin. It was now about 22:30.

Fuselage with aft turret of Lancaster LL947. Photo taken on the morning of August 30, 1944. Photo via Bo Widfeldt.

The crash site

The crash site is just east of the so-called Hjörnereds lakes, which actually is a large reservoir for the power stations in the lower part of the river Lagan. The devastation was total, smoke was still above the wreckage in the morning when the first people found their way to the remote crash site. Big trees had been ripped off before the heavy bomber grinded to a halt by the rocky forest terrain. Before the military and homeguard had cordoned off the site at 11 o'clock in the morning, many of the spectators provided themselves with souvenirs from this momentous and spectacular event in the shadow of the second World War. Both large and small pieces of the bomber disappeared. Pieces of plexiglass was popular because it was malleable, but also other parts and even machine guns found new "owners". It was in this context that this story's main piece came up - the hatch. My father took it home as a souvenir. He came to the scene by bicycle along with my uncle, who found an oily camshaft in the rubble. The opening, where the hatch was mounted, was an emergency exit to be used when a Lancaster had ditched in water.

Laholms Tidning August 30, 1944.

The position of the hatch above the pilot and flight engineer.

This image is from the Imperial War Museum in London and it shows the preserved nose-section of Lancaster DV732.

What happened on board just before the crash?

In the early 90's a writer from Knäred named Sven Martinsson interviewed people who were witnesses to the LL947's flight before the crash. He also interviewed people who had taken care of the seven airmen after they landed with their parachutes at various locations along the bombers route. A young Home Guard, who took care of the navigator Andrew Hendry, was perhaps the most important witness. He and Hendry developed a friendship, which meant that Hendry later made several visits to Sweden. At the first visit in 1959, fifteen years after the dramatic night, he visited the crash site. On another visit he had with him his son as company. The former Home Guard's testimony was obviously of vital importance when Sven Martinsson tried to describe the drama on board the doomed aircraft. In 1995 there appeared a book entitled Flygdramatik i Halland. The book involved several authors. The book has a total of just under 200 pages and over 40 of them are written by Sven Martinsson about the drama of LL947.

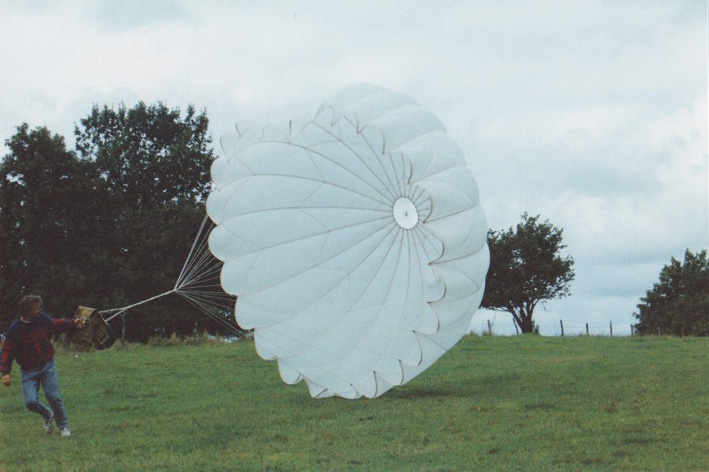

According to the information Sven Martinsson had recieved by the interviews, it had been extremly dramatic aboard LL947 when the commander on board, David Jones, gave the order to bail out. The young radio operator, Vernon Condon, panicked when he realized he would bail out into an unknown and frightening abyss of darkness. Jones handed over the controls to the flight engineer George Bayless, and went back to the door on the starboard side. They managed to overpower and knock down the hysterical Condon so that he almost passed out, and then Jones took him with him through the opening. The report that both used the same parachute, namely Jones, sounds pretty incredible, but perhaps thats what happened. Thereafter, the remaining five men in the crew left the bomber wich constantly lost altitude. During this phase the LL947 made several course changes. Therefore the crew became quite scattered over a countryside with forests, lakes and untamed nature. Its probably a pure miracle that none of them ended up in the river Lagan or Hjörnereds lakes, which occupy a large part of this area. The top turret gunner, Sergeant Stephen McFarlane, ended up in a small lake, or rather a puddle, but it was not deeper than he could wade ashore. Last man to leave the burning aircraft was the temporary pilot, flight engineer George Bayless. The altitude was now so low that it was a real risk that his parachute would not have time to fully develop.

Parachute from one of the crew of LL947. Shown in the 1990´s.

Contact with local people and authorities

The only men from the crew that ended up in the same place and stayed together was the pilot Jones and the young radio operator Condon. Both were however injured during landing but they went along in the darkness until they found a farm. Other members of the crew had to find their way in the dark to different farms in the area. Bombardier John Tovey ended up in the unlocked waiting room at Skogaby railway station, where he slept on a bench and was found by the stationmaster in the morning. Several others in the crew were injured when they touched down after bailout. The men in the crew was not completely confident that they had ended up in Sweden. The Danish island of Själland was not that far away, and there were of course the Germans. At the first tentative contact with people on the farms there was great fear from both sides. There were those who thought that Sweden had been attacked by paratroopers. The relief was great when the airmen realized they were in Sweden. Language barriers were a major obstacle. There were not many people who knew English in Sweden at this time. Not all farms had telephones, and the manually operated telephone exchanges were mostly not open at night, so it was not easy to get in touch with police, military and home defense. In the meantime the unexpected guests was offered something to eat. Bayless, who was the last to leave the airplane, was lucky because he came to a farm where the owner had previously lived in the U.S. and therefore could speak English. Others who took care of the airmen contacted people in the morning who knew a little English. Among them a teacher in Skogaby and his son who was a pupil at secondary school in Laholm. Eventually, all airmen was gathered by the Home Guard and police. They were transported to Halmstad and handed over to military authorities on I16. Several of the crew received care at the hospital for the injuries they received during bail out. After a few days the seven airmen was sent to a camp in Korsnäs, Dalarna. In mid-November, the crew was returned to England after their involuntary, but perhaps not entirely unpleasant pause in the war.

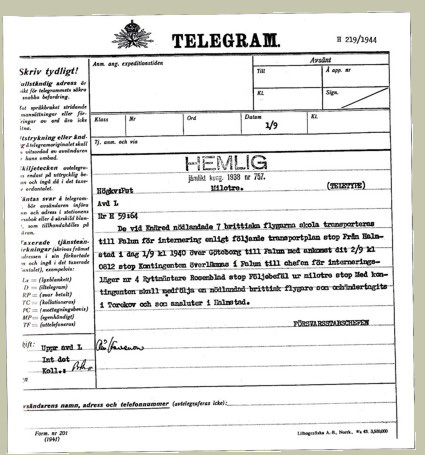

RAF Bomber Command’s result from the night of August 29/30, 1944

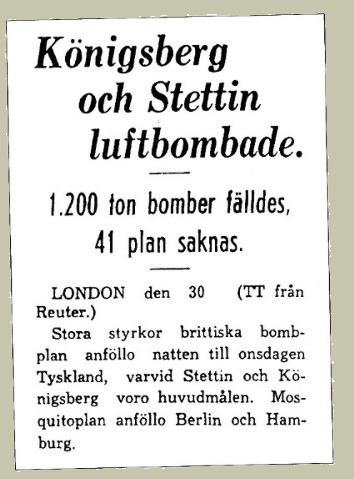

The same night as Königsberg and Stettin was attacked British Mosquitos undertook a diversionary attack on Hamburg and Berlin. In addition, British aircrafts also deployed mines in the southwestern Baltic Sea. In total, nearly 900 British aircraft participated in different raids and missions this night. On the morning 41 of these were reported missing, of which 15 from the attack on Königsberg and 23 from the attack on Stettin.

In Sweden seven Lancasters crashed and 26 airmen perished. Besides LL947, bombers crashed in Dala near Båstad, in the Skälderviken at Vejbystrand, at Lärkeröd west of Örkelljunga, in Höjalen at Vittsjö, at Svensköp on Linderödsåsen and at Agunnaryd near Ljungby. In addition one Lancaster also made an emergency landing at F12 in Kalmar.

The aircrafts that crashed in Ljungby and landed in Kalmar had both fulfilled their missions and was on their way back to base. The Lancaster (ED588) which crashed at Vittsjö was a so-called veteran, i.e. it had flown more than 100 missions. The 116th was its last.

German night fighters with bases in Denmark pursued the armada of bombers deep into Sweden and air battles were fought in Swedish airspace. One witness claimed that he heard gunfire against LL947 but this have not been confirmed by the crew.

In the Kattegat between Jutland and the Swedish west coast four Lancasters crashed this night. Some of the airmen were rescued by Danish fishermen from the island of Anholt and became POWs. Seven crewmen were found dead where they had drifted ashore at Falkenberg Sweden. They were all buried at Skogskyrkogården in Falkenberg. The 26 dead airmen from the above seven crashes were buried in the Pålsjö cemetery in Helsingborg, except one of the Mosaic faith who received his final resting place in Malmö.

The losses for this night's raids were at 4.7% in terms of lost aircraft. It was easy to count the number of aircrafts that didnt return. But the figures for loss of life took longer to obtain since crewmen could have saved themselves by emergency landings and parachutes.

After the war it emerged that RAF Bomber Command had the biggest losses of all branches. An airman was expected to take part in 30 combat missions. The chance of surviving them was 49 percent. In addition, there were fatal accidents in the UK during training. Airmen would sometimes get serious injuries, but survive. Those who bailed out or made emergency landings in Germany or occupied territories was, in most cases, prisoners of war for the remainder of the war. They also risked being lynched by those on the ground who survived the bomb raids. Statistics show that only 24 percent escaped physically unscathed through 30 missions. Some of those still continued to fly voluntarily. The legendary Wing Commander Guy Gibson, known for having led the successful assault on Ruhrdams in May 1943, was killed September 1944 on his 175th mission at the age of 26.

For a mission over Germany the casualty figures was even more daunting. Statistics show that about 65 percent were killed during these missions.

The Bomb war against Germany

No less than 60% of the Western Allies bomb tonnage, during the war, were dropped from september 1944 until the end of May 1945. The industrial production in Germany reached its peak in September 1944 and then decreased. The bombing effort continued until the end. Many cities that had no significance for Germany's war effort were destroyed anyway. The worst example was the Dresden raid in mid-February 1945.

Ground battles and air strikes wrecked greater havoc in Germany during the last five months of war than during the period up til December 1944. Much of this was not needed in a militarily point of view, besides causing unimaginable human suffering it also caused the destruction of priceless cultural values.

Aboard a Lancaster

To use the term working conditions in the context of war is of course horribly. However I will here mention the conditions under which a bomber crew had to operate. A WW2 bomber was not an airtight creation. Exhaust fumes from the engines would leak in and induce passivity. Some airmen used a stimulant agent called Bensedrine to cope. The operational altitude of the aircraft was cold all year round. So heat from the engines was led into the cockpit, were it then reached the pilot, flight engineer, navigator and radio operator. In the navigators station it was often too hot. The Bombardier in the front of the plane, where he also acted as gunner, had a cold position. The top turret gunner, and above all, the tail gunner was very exposed to the freezing conditions. In the flightoveralls there were heating coils which airmen could connect via cables and connectors. The need for this is easy to understand when the temperature could drop to below -40° C. The ability to move around on board was limited because the level of vigilance must be on top during the entire mission. The longest missions, such as Königsberg, could be nearly 12 hours long. This said raid on Stettin took about nine hours. There was a single toilet bucket on board, but who wanted to undress their protective suits and go to the bathroom in the extreme cold? Therefore many avoided to drink enough wich in turn resulted in medical complications.

Most airmen in a Lancaster was not wearing a parachute during flight. They were not comfortable to sit on and was also in the way. For the same reason they wore no life jacket when they flew over the land.

To save yourself by bailing out from a doomed Lancaster was not an easy task. Especially when the aircraft was spinning or flew upside down. If the aircraft flew level the tail gunner could, after putting on the parachute, rotate the tower so that he sat with his back to the open and then simply fall out backwards. The top turret gunner and radio operator used the main hatch on the starboard side while the rest of the crew (bombardier, pilot, flight engineer and navigator) used the emergency exit in the floor of the bombardiers station. When leaving through the main hatch the crew had to watch out not to hit the stabilizer. The order in wich the crew would bail out could change due to structural damage or fire on board.

To serve in the Air Force was made to look glamourous in the recruitment ads. The reality was quite different. But one advantage was that after the missions you could eat decent food, have the opportunity to shower and sleep in a bed with clean sheets. And if there was no mission one night you could go to the pub and meet girls.

Facts about the Lancaster

Avro 683 Lancaster, which is the bombers official name, is considered by many to be the second World War's finest heavy bomber. It dropped more bomb tonnage than any other type of aircraft. It was easy to fly, resistant to machinegunfire and stresses of flying with heavy loads. The Lancaster was the spearhead of the RAF's night offensive campaign from March 1942 to the end of the war. It was the only type of aircraft which, after some modification, could carry the 5.5 tons Tallboy bomb and the 10 ton 'Grand Slam'. Like the famous Hurricane, Spitfire and Mosquito, the majority of Lancasters were fitted with reliable Merlin engines developed by Rolls Royce.

The Lancaster's weakness was the defensive armament, which consisted of 8 relatively small-caliber Browning machine guns. The caliber was 7.7 mm (in inches .303). By comparison, the American B-17G Flying Fortress which was used during daylight raids, had 13 12.7 mm machine guns (.5 in inches).

Individual Lancasters that survived more than 100 combat missions was refered to as 'veterans'. More than 20 Lancasters recieved the 'veteran' status.

In May 1948 the Lancaster was outdated for the RAF's needs.

Today there may be 17, more or less complete, Lancasters preserved. Of these, two are airworthy and displayed at airshows and at anniversaries related to the second world war. One is in England, PA474, and one in Canada, FM213. In addition, another Lancaster in England is currently being refurbished to flying condition. It's NX611, which for several years has been presented in a taxiing condition. I myself had the privilege, in September 1998, to see PA474 in the air over Duxford England during the RAF's 80th anniversary. The sound of four well-trimmed Merlin engines when a Lancaster makes a low level pass is amazing. Those who in their time were subjected to this efficient and deadly fighting machine probably used a different word than 'fantastic'.

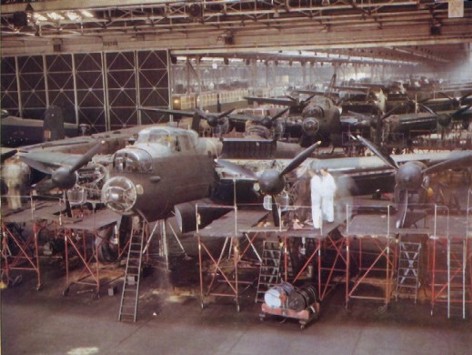

Different versions and production

|

The Lancaster was produced primarily in four major versions (Mark/Mk.).

|

Production line of Lancasters. Photo: Royal Air Force |

The Lancaster was produced in eight factories including one in Canada. In total more than 7000 were produced. More than 4,000 were lost.

Lancaster LL947

This Lancaster was a Mk.I with Rolls Royce Merlin-24 engines. It was part of a series of 450 bombers, which was commissioned in April 1942 from Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft with factories in Baginton and Bitteswell east of Birmingham. Deliveries of this series to the RAF took place between November 1943 and August 1944. LL947 had about 270 flight hours logged when it crashed at Hultabygget. On average, a Lancaster only survived about 40 hours of combat.

|

|

The squadron designation in the RAF was the 300th Polish (Masovian) Squadron and thus was a Polish unit. Masovia is the name of an administrative region in Poland. From the beginning of the war there was only Poles in the Polish squadrons. Polish squadrons were both in the fighter command and bomber command. However as losses grew the squadrons were reinforced with pilots from the British Commonwealth. None of the crewmen in LL947 during its final mission was from Poland. However the commanding officier of the squadron was always a Pole. The squadron was formed in July 1940. The introduction of the Lancaster began in December 1943. And in early March 1944 the squadron recieved its first Lancaster. In April 1944 the twin-engined Wellington bombers was replaced with Lancasters. LL947 came to the squadron in August 1944 and crashed at Hultabygget before the month was over. |

| 300:th skvadronen |

The crash site today

On my last visit to the crash site in September 2010 it was still possible, after 66 years, to see hints of the pits formed by the nose and the four engines when LL947 crashed into the wooded slopes. Tangles of cords and clumps of melted aluminum were also on site.

When I made a quick excavation at the site I soon found twenty shells of exploded machine gun ammunition.

Cleaned shells of exploded .303 ammunition for the LL947´s Browning machine guns, after 66 years. Note the clump of melted aluminum on the shell top right.

The future ofTHE HATCH

There is no doubt many homes that house items from foreign aircrafts that crashed in Sweden during the dramatic years of 1939-45. It's been a long time, and items may have been thrown away during cleaning of attics and storerooms. Over a period of 70 years many people have deceased and those who take care of a decedent's estate, in many cases, dont understand that what looks like scrap, may be of great historical value. Photographs and other documentation is also extremely important to preserve.

My HATCH will of course be submitted to FORCEDLANDING Collection, which now has its base in Morup just north of Falkenberg. I feel safe in knowing that the historians working in the FLC are the most dedicated and enthusiastic we have in this country. This ensures that THE HATCH will end up in the right place and tell its dramatic story in the future.

Nyhamnsläge, Februari 2011

Rolf Arvidsson